The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

How one fearless American journalist exposed the truth about Hiroshima

On the 80th anniversary of the world’s only atomic bombings, author Lesley MM Blume reveals how John Hersey laid bare the catastrophic cover-up of the nuclear age. Right now, she writes, we’d do well to remember his life’s work – and its grave message

.jpeg)

When it came to reporters who documented the aftermath of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, John Hersey wasn’t the first, but his account was the one that mattered. Several journalists reporting for Western press outlets managed to reach the smouldering ruins of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in the days and weeks immediately following the bombings on 6 August and 9 August 1945. Two of these journalists published terrifying initial reports of the cities’ destruction by single, primitive nuclear bombs.

At first, the US government seemed like it was hiding nothing about its experimental new mega weapons: US president Harry S Truman boasted in an announcement that the Hiroshima bomb – dubbed “Little Boy” – had packed an explosive payload greater than 20,000 tonnes of TNT and had “harness[ed] the basic power of the universe”.

The Japanese – and, by implication, anyone else who messed with the world’s then only nuclear superpower – could expect a “rain of ruin from the air, the likes of which has never been seen on this earth”.

Military photos released of the atomic cities revealed their total decimation, but these images, as the Daily Express pointed out, did “not tell the whole story”. It would take more than a year after the nuclear attack on Hiroshima for the bigger story to emerge, courtesy of Hersey’s 30,000-word investigative story in The New Yorker.

After the official surrender of Japanese forces in September 1945 – and following those initial alarming reports from Hiroshima – US occupation forces imposed a lockdown on both Western and Japanese reporters.

Journalists coming into the country with occupation forces were at first corralled in a “press ghetto”, as one reporter called it. Even when they were allowed to move more freely, occupation forces closely regulated their travel permits, fuel, food and kept close tabs on them. Hiroshima became a restricted topic; Japanese journalists could not even mention the atomic city in poetry, much less in a critical news report.

Meanwhile, General Leslie Groves – the head of the Manhattan Project, which had produced and readied the bomb – downplayed the horrific after-effects of it, at one point even telling a US congressional committee not to worry: radiation poisoning was actually a “pleasant way to die”. Stories to the contrary were “Tokyo tales”, propaganda of a defeated enemy.

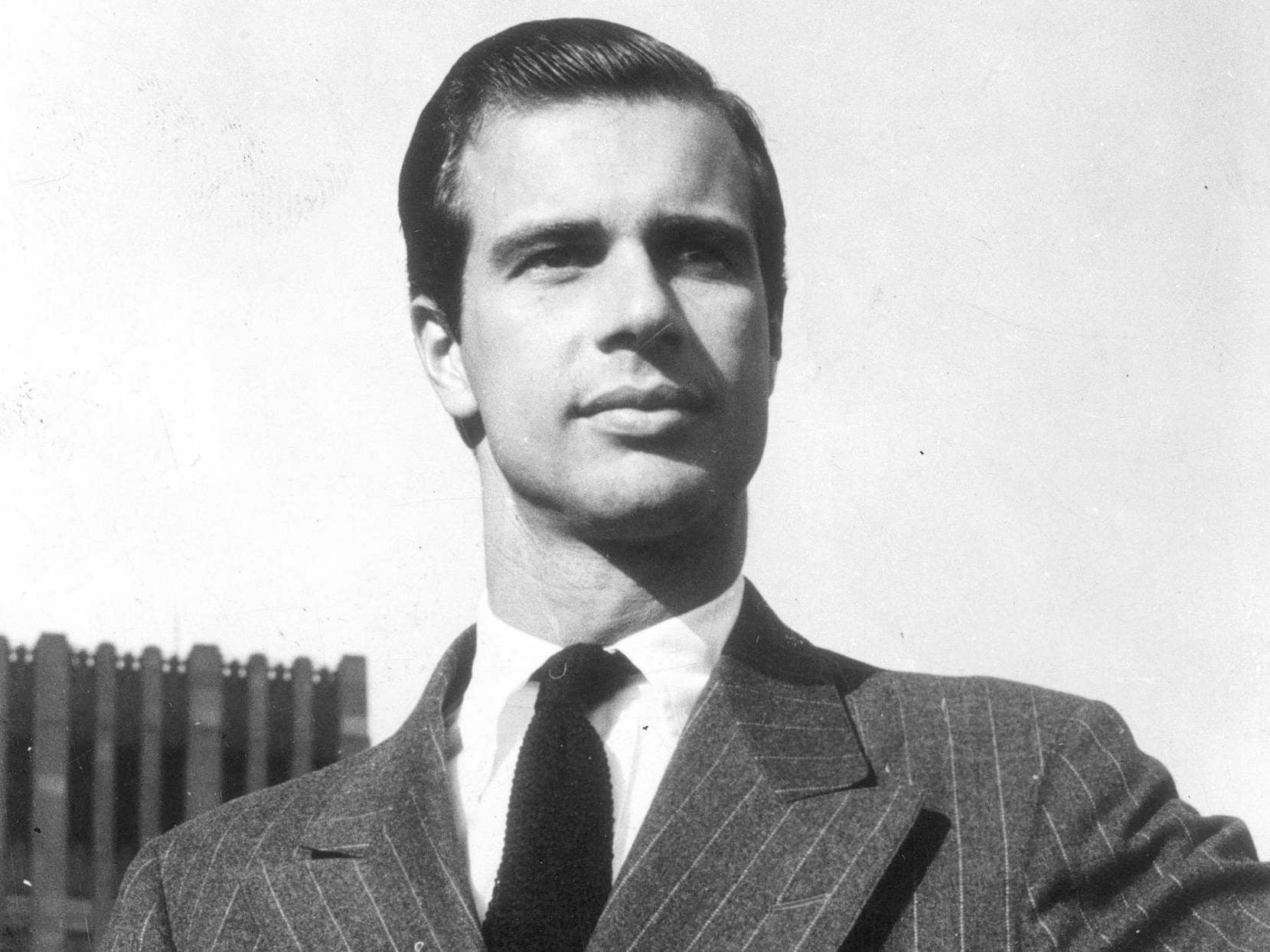

For John Hersey, a veteran war correspondent, this did not sound especially convincing, and in the spring of 1946, he applied for entrance to Japan. His quiet mission: to investigate the true effects of the bombs on human beings. He was something of a Trojan horse applicant: after all, a few years earlier, he had written a glowing book, Men on Bataan, about General Douglas MacArthur, who was now overseeing the occupation. Here was a good team player, occupation officials reasoned as they greenlit Hersey’s admission to the country.

They soon came to regret their decision. Hersey had been given permission to briefly visit Hiroshima, where he quickly interviewed dozens of survivors. He ultimately selected six testimonies given to him by highly relatable civilians, including: a single mother with three young children; a 20-something female clerk; a young, bespectacled medic; and a young pastor with a wife and a baby. Hersey collected their stories, took his notes back with him to New York, and there composed one of the most influential works of journalism ever written.

His protagonists had relayed memories of the bombing in graphic, harrowing detail, and Hersey held nothing back: the charred corpses lining the streets; the voices of those trapped beneath their demolished homes, left to burn to death as fire tornadoes tore through the city. The young reverend told Hersey of his attempts to pull a victim into a small boat to paddle her away from the flames, across one of the city’s rivers, only to have the victim’s skin “slip off in huge, glove-like pieces”. Sickened, the reverend had to sit down to compose himself after that, and repeatedly remind himself:

“These are human beings.”

As Hersey and The New Yorker team were preparing to release his article, most of his fellow Americans had already moved on from Hiroshima. Other reporters and newspaper editors deemed it an “old story”. Yet when his article – entitled Hiroshima – was released in the magazine’s 31 August 1946 issue, it was explosive in its own right. Here, at last, was a raw, uncensored glimpse into what it had been like to come under nuclear attack. More than 500 radio stations covered Hersey’s story, which earned front-page headlines, excerpts and editorials around the world. Both ABC and the BBC adapted “Hiroshima” for dramatic radio readings. Even those who hadn’t read it were talking about it, as one critic put it – and those who had read it would never forget it.

Hersey had transformed unfathomable horror into unmissable, compulsive reading. He also showed that this so-called “old story” was not old at all, and that it never would be again, because it showed what was in store for all humans, in every country and on every continent, should nuclear war ever break out.

This is what it meant to have entered the atomic age.

Eighty years later, the United States remains the only country to have used nuclear weapons in warfare. Hersey later said that the memory of Hiroshima’s devastation helped fortify government reluctance to use nukes again. Indeed, his Hiroshima – which remains as sobering today as it was in 1946 – has been credited with contributing to a so-called “nuclear taboo” surrounding atomic attack.

Nuclear arsenal stockpiles are significantly down from their peak Cold War levels. According to the Federation of American Scientists, the US inventory peaked at 31,255 in 1967, and currently contains an estimated 5,177 nuclear warheads, with around 3,700 in the active military stockpile. Russia currently maintains nearly 5,460 nuclear warheads, with an estimated 1,718 deployed. Yet some experts warn that we have entered into a new nuclear arms race in recent years. The US alone plans to spend more than a trillion dollars maintaining and upgrading its nuclear arsenal over the next three decades.

Leaders of the world’s superpowers are once again engaging in nuclear sabre-rattling. We have entered such a perilous nuclear landscape that the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists has set its famous Doomsday Clock to “89 seconds to midnight” (ie 89 seconds to armageddon). The clock has never been set this close to midnight, not even during the depths of the Cold War.

All of these developments beg the question: is anyone still listening to John Hersey? While Hiroshima – which was immediately released as a bestselling book after the article was first published – was widely read and taught in schools for decades, it’s unclear how prevalent it is in curricula now. Vocal survivors of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings – called hibakusha in Japanese – are also dwindling in numbers, and as each witness dies, there is one fewer living connection to this catastrophic cautionary tale.

By the 1980s, as Cold War hostilities surged, Hersey gave an interview in which he warned about the possibility of “slippage” – a hair-trigger mistake or misinterpretation between two nuclear powers that could lead to an immediate nuclear confrontation. If such slippage occurred now, leaders of nuclear nations could, in a matter of minutes, wipe out civilisation. This danger may be amplified by the insertion of AI into military and defence infrastructures. Recent public opinion studies have also revealed that the nuclear taboo may be waning as well.

Yet even with the apparently diminished impact of Hersey’s work and warnings, there are encouraging signs that the world is waking up to the threat that nuclear weapons still pose. The Oscar-winning Oppenheimer engrossed audiences around the world and earned nearly $1bn in ticket sales. Last year, the Nobel Peace Prize was given to Nihon Hidankyo, an organisation devoted to fighting for hibakusha rights and raising awareness about the devastating impact of the Japanese bombings. As global awareness once again surges about the nuclear threat, more action to counter that threat is possible.

And John Hersey’s Hiroshima will always be there to remind us of the stakes.

Fallout: The Hiroshima Cover-up and the Reporter Who Revealed it to the World, by Lesley Blume is out now

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments